Built Estate Analysis

The Built Estate Analysis, undertaken by Built Environment Forum Scotland (BEFS) with the National Trust for Scotland, examines the Trust's built estate in detail. We used the newly formed Built Estate Asset Register to assess our current estate, including: what types of buildings the Trust has, where they are located, how old they are, what designations apply to them, and how they are used.

Introduction and overview

The National Trust for Scotland owns and cares for a unique and complex estate. The Trust’s wider heritage portfolio, and the connected intangible heritage, stands alone within Scotland in the number of visited sites and the combination of natural, built and movable assets.

The Built Estate Analysis set out to understand more about the estate specifically, and its diversity of building type and use. The analysis was undertaken in support of a review of the portfolio and provides a crucial example of how datasets can support prioritisation decisions for the future.

The Built Estate Register is a live database and contains 31,179 entries, categorised in a variety of ways to increase the Trust’s understanding of the range, type, location, significance, condition and needs of the built portfolio. The Register represents the first time the Trust has collated categorisation data on the built estate with the purpose of improving understanding and helping to define a national view of the collection. While some gaps remain, the dataset is largely complete.

The information in the Built Estate Register supports the delivery of the Trust’s strategy. This may inform thoughts on the Trust’s future portfolio, such as exploring questions around conservation, engagement and representation.

Setting the Trust’s buildings within a national context is more challenging. Other than sites which are designated, there is no national database providing the essential details (age, location, materials, condition) for Scotland’s historic (pre-1919) and existing buildings. Information relies upon the levels of resource (and accuracy) that have been given to data management. These challenges have national consequences around planning, provision of maintenance including skills and materials, adaptation for climate change, assessing energy use and meeting national Net Zero ambitions. The current detailed level of understanding that the Trust has chosen to resource for our built estate is a sector-leading exemplar.

Our comprehensive dataset can be shared with others, to integrate within nationally recognised categories. If similar information was readily available across all aspects of the portfolio, and across other heritage asset holders, gap-analysis could be rapidly assessed, and the stories of Scotland as yet untold, or under-represented, could be identified and secured for the future.

Specific questions might include: How does the use of a building impact its condition? How accessible are the Trust’s buildings when mapped against centres of population? How does the Built Estate Register help us understand the Trust’s estate in telling the varied stories of Scotland’s people and places?

Key findings

What types of buildings does the Trust hold?

Within the Built Estate Register, sites have been classified as either principal (the significant asset to the site) or ancillary.

Within our portfolio, just under 9% of our buildings are identified as principal structures, with 89% playing an ancillary role (the remaining 2% of entries were left blank).

The principal assets have been classified into broad types using categories that are used within the sector. Over half (56%) of our principal assets are used as museums either in a castle, mansion house, domestic, industrial or commercial museum setting.

Ancillary assets have also been classified according to type. It is not surprising to see that a large proportion of our ancillary buildings in the portfolio (for which an asset type has been assigned) are either residential (27%), agricultural (17%) or used for service infrastructure (15%).

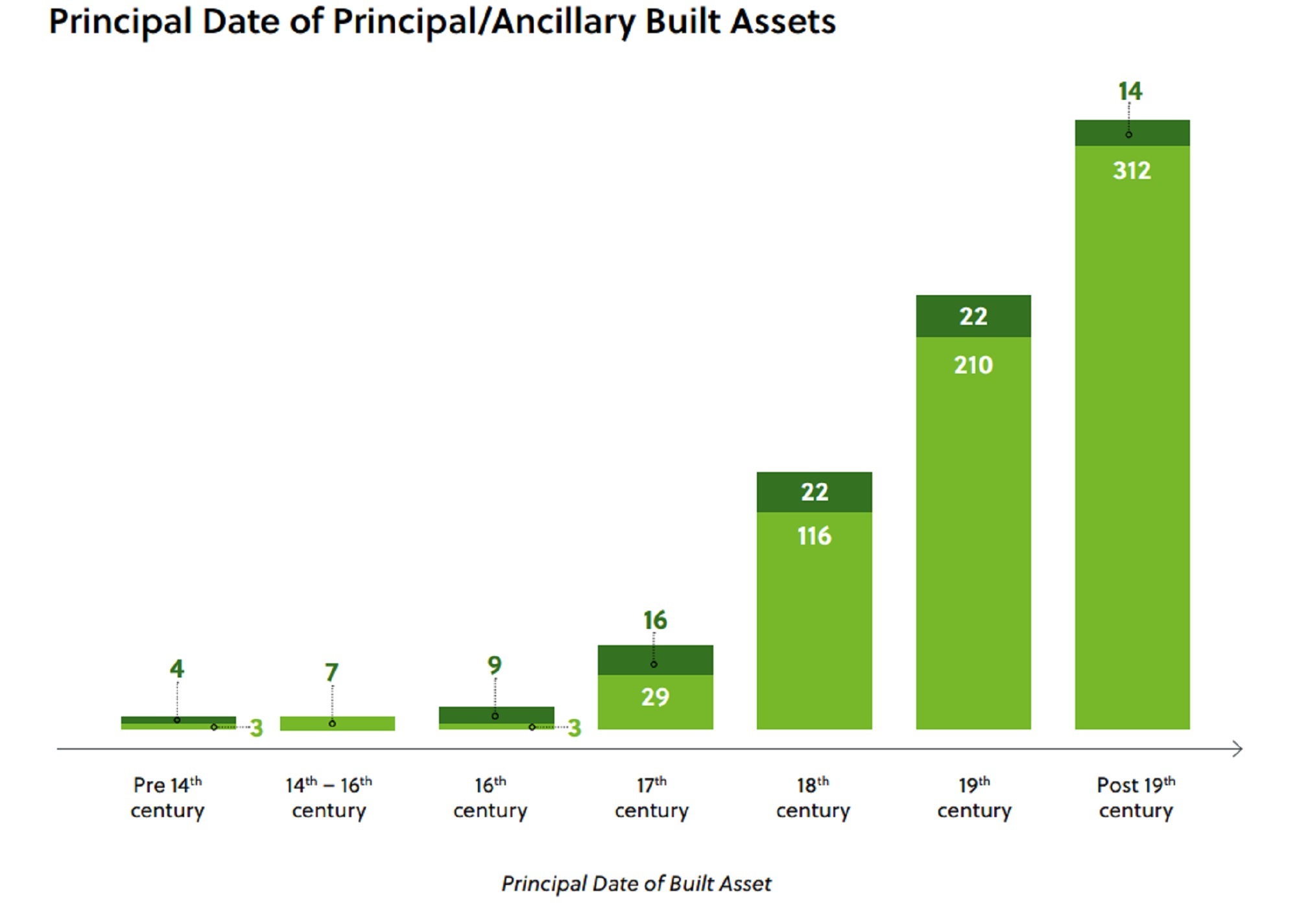

How old are the Trust’s buildings?

Of the 767 buildings for which a principal date is recorded in the Built Estate Register, 43% were constructed principally after 1900, although this does include a large number of ancillary assets.

Our portfolio contains a small number of pre-16th-century buildings (1.7% of the buildings for which a principal date is recorded) and a limited number from the 16th and 17th centuries (7.4%). The Trust has a much higher percentage of buildings that can be principally dated to the 18th and 19th centuries (48%).

The majority of the Trust’s 17th-century properties are located in the Edinburgh & East region, while the Highlands & Islands have a disproportionate number of properties that date to after 1900.

There is currently no national dataset that records the location of all historic buildings across the country.

Where are the Trust’s buildings located?

Our built assets are generally evenly distributed across the Trust’s regions.

The North East region contains the highest number of buildings (364, or 31%). This is likely to reflect the number of built structures associated with the functioning medium or large rural estates in this region. Edinburgh & East is the region with the smallest number of built assets (193, or 16%), which is likely due to the lack of sizeable estates within the region and the higher concentration of individual assets associated with the Trust.

The recurring disparity in building numbers for rural and urban sites can distort the presentation of location data when considering headline numbers. With that caveat, nearly half of the Trust’s built assets are classified as rural (45%). When combined with those structures defined as remote and rural settlements, this highlights that the Trust’s built assets are disproportionately located in rural areas and communities (70% in total).

Meanwhile, assets in large towns/urban areas make up only 9% of the Trust’s built assets.

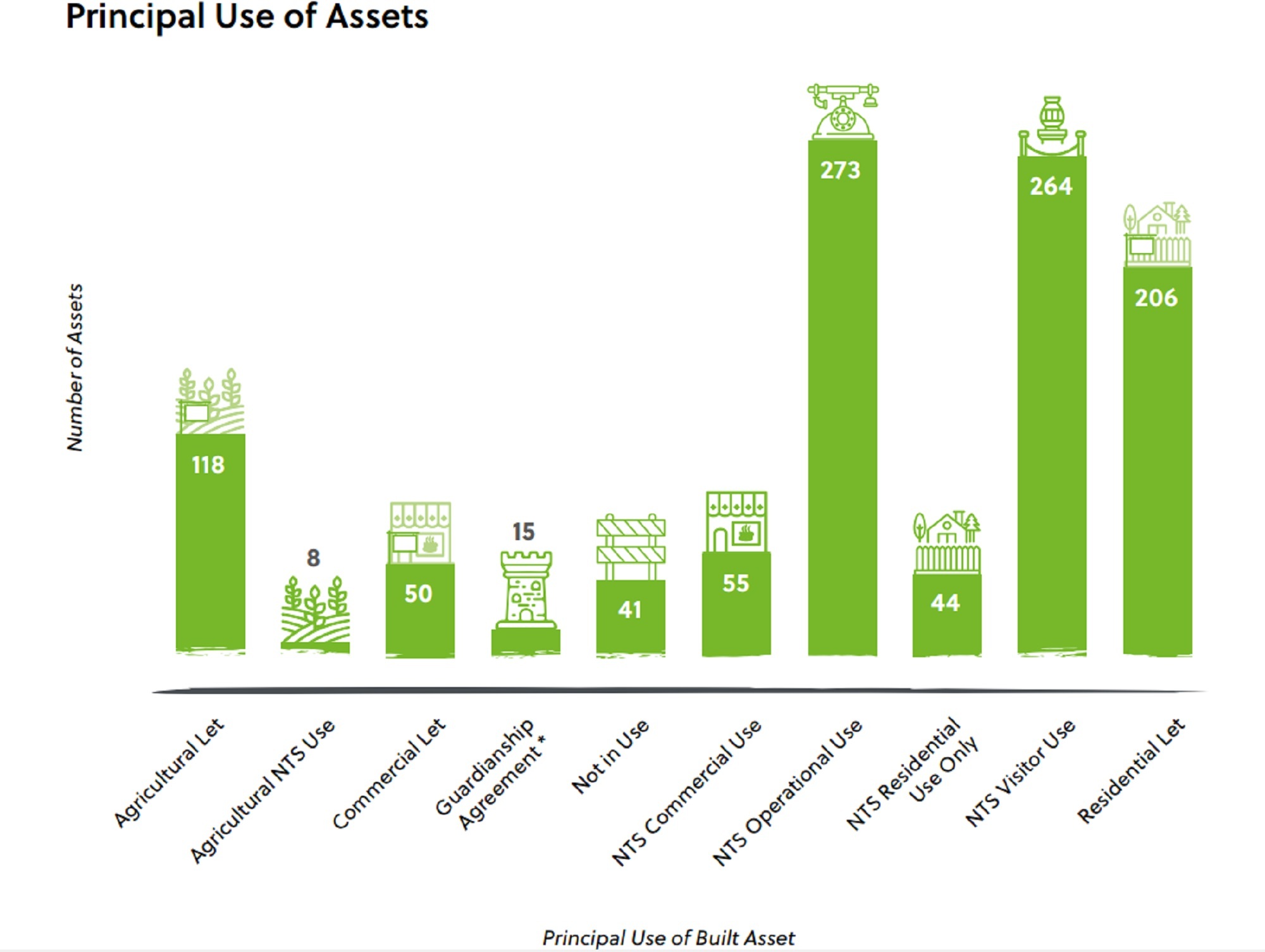

How are the Trust’s buildings used?

70% of our built estate is in use. Only 8% of the ‘roofed’ built estate is classified as not in use or vacant.

The remaining 23% of the built estate has been classified as ‘structures’ (including unroofed buildings and memorials). This category is broad and also includes structures that support the operation of a site but do not naturally fit into other categories (such as walled gardens or bridges). By comparison, Historic Environment Scotland (HES) classify 34% of their estate as roofed, with 66% calculated as either unroofed, a monument or a standing or carved stone.

Unsurprisingly, the majority (50%) of the buildings in the Trust’s portfolio are used primarily as a visitor attraction or for supporting operations. The let estate, including residential, agricultural and commercial leases, accounts for 35% of structures.

There is variation in how buildings are used depending on their location. The West region, for example, has a much higher proportion of agricultural lets compared to other regions, principally due to the number of leases noted for Threave Garden & Nature Reserve. The Highlands & Islands have a smaller proportion of buildings for the specific use of Trust visitors than other regions – the number of operational buildings looks to broadly correlate with the number of buildings used for visitors.

What designations apply to the Trust’s sites?

The majority (83%) of the Trust’s principal assets have some form of statutory designation – 55% are protected at the highest level as Category A listed buildings, with 9% as Scheduled Monuments.

30% of the Trust’s ancillary structures are also designated, although unsurprisingly a higher proportion are Category B or Category C listed buildings, with only 6% of ancillary structures designated Category A.

Information is nationally available for designated buildings, with 8% of Scotland’s listed buildings classified as Category A. Of the Trust’s designated principal assets, 66% are Category A; of the Trust’s designated ancillary assets, 20% are Category A. This indicates that the Trust’s designated built assets are more likely to be designated with the highest level of protection than the national average.

Reflections

Conservation is both a core Trust principle and a key influence on Trust activity

We report on the condition of our built assets to support the Conservation Performance Indicator (CPI). We also report separately on our Buildings At Risk. The CPI is based on condition knowledge of Category A listed assets, according to a programme of condition survey work. If the condition cannot be evidenced, or the condition survey is older than 10 years, then the structure is reported as having no data.

Concerns regarding this condition measure, and the sizeable data gap, prompted a concerted effort to gain more condition data, with a new suite of health check surveys proposed during 2022/23. The Trust can therefore expect significantly greater levels of data to become available, improving the accuracy of this element in coming years. At the same time, with coverage of health checks expanding beyond Category A listed buildings, the number of assets being assessed under the CPI will also grow significantly.

During the creation of the Built Estate Register, the surveyors were given the option to report as to whether a building or structure was in good, fair or poor condition, based on their current working knowledge. In addition, the Trust operates a register of Buildings At Risk (BAR), to which buildings or structures in poor condition and giving concern are added. The Built Estate Register also provided an opportunity to update and register any changes to the BAR. Accordingly, data is held relating to building condition in the new Built Estate Register, albeit that this data cannot fully be relied on as a source of accurate information. It can, however, be used to draw some of the following observations:

- 794 (67%) buildings and structures reported in the Built Estate Register are considered to be in fair or good condition, with 137 (11%) in poor condition and 14 buildings assigned as a Building at Risk.

- 234 (20%) buildings do not currently have condition data in the Built Estate Register.

Having professional condition survey information allows us to accurately define the condition of the estate. Where the Trust has professional survey data, more structures are defined in poor condition. This highlights the complex nature of historic and traditional buildings, in that defects are often uncovered as a result of professional investigation.

Investigation and accuracy of reporting is increasingly essential, as outcomes around estate condition (in relation to all asset types) are a key driver of investment and activity across the wider estate. The work carried out on the Built Estate Register, and the wider Portfolio Review, supports data-informed decision-making for the future.

How accessible are the Trust’s buildings when mapped against centres of population?

The accessibility of, and the ability to engage with, Trust sites can be considered in many ways. It is not appropriate for all Trust buildings to be accessible: many are leased or are used by the Trust for purposes which require limited access, either because of health & safety or to ensure the security of information and goods.

One form of analysis is to assess the accessibility of buildings by examining their proximity to population centres. Previously, it was noted that Trust sites are far more likely to be in rural rather than urban areas. More detailed analysis can break this down further.

The map in the downloadable report below shows in detail the population of Local Authorities against the number of principal built assets within the Trust’s portfolio. There are some headline observations:

- The Trust’s buildings are geographically dispersed across Scotland.

- There are Local Authority areas that contain no Trust buildings, although the majority (apart from Orkney) are in close proximity to other Local Authorities that do have a Trust presence.

- The 1st and 2nd most populous local authorities (Glasgow City and City of Edinburgh) do not have the largest number of principal built assets. However, they do have a relatively high proportion.

- The 4th most populous local authority (North Lanarkshire) contains no principal assets, while the 5th and 8th most populous local authorities (South Lanarkshire and Aberdeen City) contain only one principal asset each.

Looking at the whole Trust estate, buildings can be focused around a relatively small number of sites. This is particularly true in the North East region, where there are a number of large estates. Meanwhile, the high number of buildings in Dumfries & Galloway and the Highlands & Islands are concentrated in relatively small geographic areas; and the Central Belt region, spread across a number of Local Authorities, has a sizeable number of small sites. The majority of sites within large towns/urban areas are for either visitor or operational use. While there are proportionately fewer sites in urban areas, these are more likely to be sites which are accessible to the public.

Of course, proximity to population centres doesn’t necessarily predict levels of visitation. The size of sites and the facilities they offer affects their appeal to visitors. The smaller sites in the Central Belt tend to have a more limited visitor offer and therefore draw a relatively small number of visitors, even if they have a relatively large immediate population catchment. Sites with more facilities can encourage repeat or overseas visitors.

This finding is supported by the Socio-Economic Impact Assessment (2021), which highlighted that Trust sites in remote areas have a disproportionate impact on their local economies. 46% of the Trust’s direct employment at gated properties, for example, was calculated to occur within remote or accessible rural areas, while more than £14 million of the Trust’s direct expenditure occurs within (or supports) remote or accessible rural areas. Remote areas proportionately have the smallest number of built assets primarily used for visitors when compared with other location types, but the built assets that are in use here are more likely to provide a significant, large-scale visitor offer.

The Built Estate Register can help us promote the Trust when telling the stories of Scotland’s people and places

Information contained with the Built Estate Register can be used to relate the Trust’s portfolio to a national context. As we stated earlier, 43% of the Trust’s buildings with a principal date recorded are from after 1900. This challenges the assumption that we hold little in our portfolio from the 20th century.

As a conservation charity, the buildings we care for and maintain are a significant driver of economic investment within the Trust. The information on condition, age and spread of location, further understood through the Built Estate Analysis report, supports future decision-making around resources. Our built estate is highly designated, signifying that a high cultural value has been attributed to many specific buildings and sites. This prominence may be of note when considering a national picture and advocating for significant sites within wider prioritisation discussions.

Whilst acquisition is limited by both availability and resource, the information within this report and the wider work of the Portfolio Review enables informed decisions to be taken around what stories of Scotland the Trust will tell next. Those stories may reflect places where rural communities once flourished; under-represented groups (eg women or minorities within Scotland); areas where socio-economic change has reshaped our places through heavy industry; or the ‘new heritage’ formed after the Second World War.

All examinations of the Built Estate Register have been at either Trust regional level or national scale. There remains significant opportunity to use this data, and other social and economic research completed by the Trust, to interrogate what we know about what matters to people at a local level. Examining age, location and designation is the start of wider considerations that could site Trust properties as national icons, sites of particular technological innovation, highlight individual and social connections with cultural movements or the arts, as well as explore the interaction of people with place – both what has been left as ‘wild’ landscape and what has been formed as places of work, industry, leisure and homes.

Built Estate Analysis

pdf (9.265 MB)

Download a copy of the full Built Estate Analysis report, compiled by Built Environment Forum Scotland and the National Trust for Scotland